Determining the effectiveness of an automated problem reporting system

Daniel Thombs

ISS 500: Research Methods

October 7, 2002

Abstract

Introduction

Background

In any given company, computers and other forms of technology are always malfunctioning and proving ineffective for employees at times. As with anything that slows productivity and inhibits the company’s workflow, these problems and errors must be fixed with additional methods put in place for prevention of future slow downs.

In an attempt to deter major problems, a new division within the company usually labeled MIS (management information services) or IT (information technology) is created solely for the purpose of keeping the current technology running smoothly. In most organizations, the MIS staff relies on word-of-mouth from other employees regarding their technology problems. This reliance on ‘chance’ and hoping the MIS staff is in a fixed location proves inefficient for resolving issues quickly. At times, technicians are solving other problems, in a meeting, or simply away from their desk, all possibilities that prevent another employee from relaying the message of an error. If a technician cannot be found, the problem goes unsolved until he or she becomes available or checks a message stating the current problem; it doesn’t take long for a voice mailbox to fill up, or a desk to become cluttered with sticky notes, both of which are more effective for other purposes.

Some MIS divisions have implemented a model, conceived by IBM but later modified by independent companies, to automate the problem reporting system and additionally archive the requests for future reference. With a system such as this, an employee uses the company network to post a service request, which is received by an MIS technician instantly, or as soon as they are free. If he or she is busy fixing another problem, the request lies dormant until he or she is finished. Once the problem is solved and the request is fulfilled, the post is closed. Every submission is archived in a database for reference in case the problem recurs; the archive acts as a knowledge base for all past solutions.

Research Question and Rationale

Does a computerized problem reporting system prove more effective than word-of-mouth in a business environment? Comparison will be based on previous word-of-mouth reporting methods used before the process was automated. Efficiency, productivity, and simplicity all play key roles in determining the ‘best’ way to resolve problems and resume normal work. All problems differ and some can be lived with temporarily, while others bring workflow to a halt until they are resolved. Finding the effectiveness of an automated system, both through the opinions of the MIS staff and the employees using it, is an important step in making the company run smoother.

With an organized listing of issues to respond to, it will be believed that the MIS staff will never become bored and will have a clear focus on their job tasks. Employees will also benefit by being confident that their requests will not be forgotten in addition to the ease of assigning the task. They will no longer have to find the technician by chance, not have to wait until they are free to report a problem in person.

With the clear benefits of a computerized reporting system, word-of-mouth information delivery has few, if any, notable advantages over the former method.

Definition of Terms

Efficiency and convenience are subjective terms; one must look at what each means to the people it affects. The survey results of one employee may state that efficiency means being able to stay at his or her desk while still being in communication, and results of others may state that it may simply be interpreted as a time saving method. Total success of the system is somewhat subjective as well. The system’s acceptance is based on the feelings and attitudes of those who use it. Some people may prefer to walk around and find a live person if they find the idea of logging in a request as indirect and ineffective.

Review of the Literature

Very little material was available on computerized problem reporting systems for MIS departments, but many touch on the components and benefits of such a system. I divided the literature into four main groups. Several studies have been undertaken on the MIS (management information systems) department itself (Allingham & O’Connor, 1992; Cullen, 1992; Grove & Selto, 1990; Martin, 1982). These studies set out to search the effectiveness of MIS both at the employee level and also with the systems used. Other researchers dealt with technical support and help desks for technology, particularly in the areas of information support for business executives (Xu & Kaye, 2002), support for home Internet users (Kiesler, 2002), and intelligent helps systems for Unix users (Fernandez-Manjon, Fernandez-Valmayor, & Fernandez-Chamizo, 1998). Other fields of study had similar articles with new technology. Researchers in the medical field had interest in creating a knowledge base for diseases and problems that will later be accessed by a larger population (Ambegaonkar & Day, 2001; Bean & Martin, 2001). Educational facilities were also on the forefront for technological systems. In this, field Information Communication Technology was looked at for increased educational coverage (Brakels et al, 2002; Kelleher, 2000), as well as comprehensive knowledge bases for teachers (Moore & Hopkins, 1992; Turner-Bisset, 1999). The articles in the medical and educational fields, while not exactly like those in MIS, both shared goals and methodology of an information-oriented system.

Most researchers in the MIS field concentrated less on the specific systems used in an informational environment, but more on the benefits, satisfaction and uses of having an MIS department. Success was defined in differing ways. Allingham (1992) looked at success as the satisfaction levels of management and other employees within a company, all who were on the receiving end of MIS’s services. On a more monetary scale of success, Grove (1990) looked at the overall effect on the company’s market value when certain variables, such as sales growth, risk, advertising and research & development, were altered by MIS. Martin (1982) went a step further and looked not at whether MIS was successful, but how it had succeeded by looking at the strategies used by its highest-level executives.

Common employees were found to be the majority of the samples used in MIS effectiveness studies (Allingham& O’Connor, 1992; Cullen, 1992; Grove, 1990). Through them, end-user responses and feelings were gathered to get a better idea of those most affected by MIS. Martin (1982), however, chose 15 highest-ranking executives to survey since his study was slightly different. Questionnaires were issued in all cases, for unobtrusive measures in some cases (Martin, 1982), with face-to-face interviews given to others as performed in the case of the 77 employees interviewed by Allingham and O’Connor (1992). These interviews took place three to four weeks after the questionnaires were given out and were used to find out more in-depth information about other factors associated with their personal satisfaction.

An MIS has been found to be beneficial on the whole (Allingham & O’Connor, 1992; Grove, 1990), as well as the systems they can organize (Cullen, 1992). Satisfaction wasn’t found to vary much across management levels, but rather organizational function and involvement (Allingham & O’Connor, 1992). Martin (1982) reported several areas that major executives found to be important to and MIS’s success, such as system development, data processing, HR development, management control, relationships and support. These factors combined with several variables including sales growth, risk, advertising and research & development affected the company and it’s value in a positive way (Grove, 1990).

Educational facilities were the topics for several researchers. Two main concepts were brought up in the articles chosen. Knowledge bases for faculty use were proposed to further enhance the teachers’ training (Moore, 1992; Turner-Bisset, 1999). Rather than static training, data could be stored in a central location for all to use and benefit from. Turner-Bisset (1999) reported that a model such as this would be the most comprehensive method for training knowledge; Moore (1992) added that this knowledge base must also be constantly updated so the information would be current and always at peak value. Systems such as these were also found useful in the medical field (Bean & Martin, 2001).

Information Communication Technologies were another topic of research (Brakels et al., 2002; Kelleher, 2000). An ICT system was implemented in Brakels’ (2002) study at Delft University. The main goal was to provide an alternative to face-to-face interactions. Conversely, Kelleher (2000) found that ICT could never replace face-to-face interactions and relationships between the teacher and students; ICT could only provide additional enrichment activities. When ICT was implemented, three general phases were followed. First the technology had to be gathered and implemented into the facility of choice. Once in place, the facilities were used to broaden the learning environment for both faculty and students. Going past that, the technology was then looked at again to see what further improvements and innovations could have been achieved (Brakels et al., 2002). In both cases, ICT was seen to be a positive addition.

For all systems researched and proposed, sample groups were given hands on use to the systems for feedback. Faculty, since it was the main target, was widely used in all of the studies (Kelleher, 2000; Moore, 1992; Turner-Bisset, 1999), while first year students were allowed input in Brakels’ (2002) study. Meetings were used primarily to allow an open forum for feedback and discussion.

The medical field, much like the educational field, was found to have automated systems and knowledge bases implemented (Ambegaonkar & Day, 2001; Bean & Martin, 2001). In a study of those using a medical knowledge base, most found that systems such as these are beneficial (Bean & Martin, 2001). Public health, regardless of location, can then receive, analyze and implement disease interventions rapidly with a comprehensive listing of all previous knowledge by current participants.

Systems such as these need constant feedback, either through voluntary or mandatory means, according to Bean and Martin (2001). A study of risks and patterns in ten hospitals as well as a clinic based study of patient care, found that web-based implementations worked well in order to access data. Since the Internet is widespread and readily accessible to most people, the sample found this an easy means of receiving data from a medial establishment (Ambegaonkar & Day, 2001). Both studies show signs of future potential and growth.

Independent of specific fields and practices, information and support are important for users at home (Kiesler, 2000), at school (Fernandez-Manjon, Fernandez-Valmayor & Fernandez-Chamizo, 1998) and in the office (Xu & Kaye, 2002). In a study of 93 families totaling 237 people, each was given a complete system for accessing the Internet. If they had questions, there was a help desk line that they could call (Kiesler, 2000). In the school environment, students using UNIX were given the opportunity to activate a helper program in order to learn the operating system more proficiently (Fernandez-Manjon, Fernandez-Valmayor & Fernandez-Chamizo, 1998). Xu and Kaye (2002) researched the office environment to determine the use of information systems by executives and manager. Out of 1518 questionnaires mailed out, 242 responded and 155 were valid enough to use. Fernandez-Manjon’s (1998) sample was taken out of convenience and can only be applied to the university to which it was taken from. Kiesler (2000) and Xu (2002) selected random samples and applied varying study methods. While a questionnaire was used for opinions in Xu’s study, more comprehensive measures were taken in Kiesler’s study. The Internet usage for each participant was tracked to determine the connections made per family. The help desk, which was set up for technical support, kept records of all calls made, and to get responses from those who never called, questionnaires were set up and interviews took place at their home (Kiesler, 2000).

Results differed throughout the studies due to varying methods. Fernandez-Manjon (1998) was not able to show extensive results due to his sample of convenience. His data can only be applied to his university; external data will need to be gathered for results to apply to any other institution. Executives interviewed about accessing information were found the majority of the time, to not access any central informational systems, even though they had full access to them. They instead relied on hard copies compiled and handed out to them by others. One reason for this behavior was the notion that company information is static, and there is no need to check on information changes in any small interval (Xu & Kaye, 2002). Kiesler (2000) was able to find out about the habits of some of the families studied. Only half of the people who signed up for the Internet study ended up calling the help desk for support. Teenagers were found to be slightly more skilled, but also more likely to call for help. They, or at times another family member, tended to become the family guru, and would be the only one to call for support.

Throughout the research, key ideas and concepts hit close to home on the researched topic, but nothing exact. The problem reporting system that was researched has many components such as a knowledge base used for centralized and comprehensive data as reported on by several researchers (Ambegaonkar & Day, 2001; Bean & Martin, 2001; Cullen, 1992; Moore, 1992; Turner-Bisset, 1999; Xu & Kaye, 2002). The medical fields seemed responsive to reporting problems electronically (Ambegaonkar & Day, 2001; Bean & Martin, 2001), while it seemed technical and informational help was part of user satisfaction (Allingham & O’Connor, 1992; Kiesler, 2000; Xu & Kaye, 2002). Using the relevant parts to each source provides an ample base for the following study.

Method

Sample

The sample for testing the effectiveness for a computerized problem reporting system was chosen amongst the employees of one given company in which one of these systems has been implemented. I will attempt for complete cooperation, but will make sure to get at least 30 respondents. Although the sample comes from only one company, there are many differences between persons surveyed. The rank of an employee can range from a factory worker to a manager, each using the system, but in a slightly different manner. Some employees are simply users of the system so far as only posting problem requests, while members of the MIS staff are on the other end, receiving requests and answering them. Most of the people sampled will have been in the company since before the system was put in place, but a few will only know the environment that uses the reporting system. The feedback will be slightly different since they will not be comparing life before and after, but rather their unbiased opinions on the system as it is.

This sample is partially chosen due to the accessibility of the candidates, but also as a way to get feedback from a diverse group of people all having the common trait of using the same system. A high response rate percentage is planned due to the social network that exists between the researcher and the sample.

Instrument

Questionnaires were used to gather information from the sample. Several custom-designed questions were asked which had been tailored to the reporting system in place. Comparison questions were important for some employees that have knowledge of the word-of-mouth method used in previous years. Getting their thoughts on the changes was important to determining the effect the system has caused. Other subjective questions were key, such as their views on efficiency, time saving, ease, and overall effectiveness.

Data Gathering Procedures

Questionnaires were given out and collected personally. Indirect methods were avoided due to the ease of ‘forgetting’ to finish it, or never starting in the first place. Employees were sure to finish as part of the system’s official feedback process authorized by the company. A moderate timeframe was allowed in case employees were genuinely busy with work, but were encouraged to finish as soon as possible.

Data Analysis

Once all information had been acquired, the results were compared for similarities and common themes. Employee function level was a key role in the comparative analysis, mainly to see the use of the system and frequency. Notes were recorded to take into consideration the differences that each employee offered the survey. The main objective in the data gathering was the subjective opinions of each user. All responses were categorized for their positive or negative criticism, with any extra notation taking effect.

Results

Findings

A total of six departments took the survey: Accounting, Administration, Customer Service (CSR), Maintenance, Plant and Sales. A total of four employees responded in the Accounting department, five in Administration, 11 in Customer Service, three in Maintenance, three in the Plant and four in Sales.

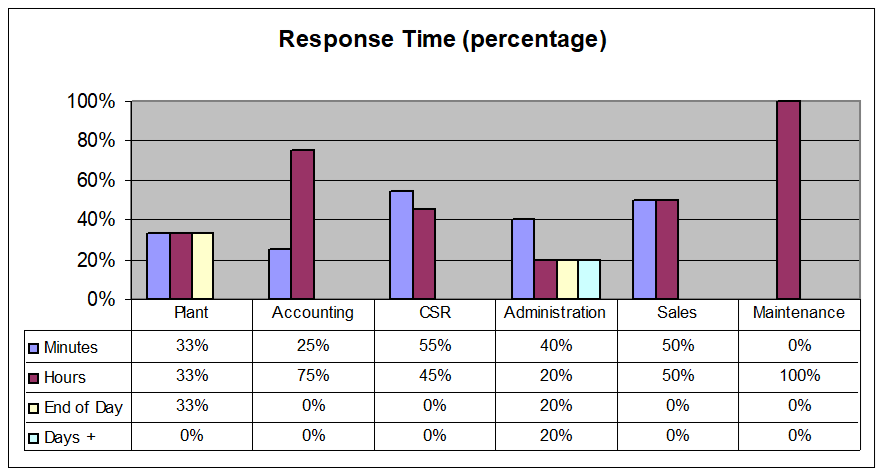

Response time was reported as minutes, hours, the end of the day, or longer than one day. The Plant employees reported differing times, with one stating that problems were addressed in minutes, another in hours and the last, by the end of the day. Administration also had differing times with two employees reporting problem addressing within minutes, and the remaining three reporting hours, by the end of the day, and greater than one day. Accounting moved more towards the hours range with a total of three responses; one employee reporting in the minute range. Customer Service and Sales reached split decisions with 6 ‘minute’ responses and 5 ‘hour’ responses for Customer Service, and 2 responses each for minutes and hours in Sales. Maintenance had the most consistency with all three employees reporting in the hours range.

Compared to the old system, reported times shifted downward towards the shorted ranges. The answers received were from an open-ended question, so there were not exactly 30 responses, nor were responses limited to the choices mentioned above. . Before the reporting system was in place, only two people stated that their problems would be addressed in minutes. This is due to their confidence that they will be able reach MIS at any given time. Ten employees reported that it would be in the hours range, seven by the end of the day, three stated that it would take more than a day, one reported that the time varies depending on the schedule, and two would simple not report problems.

|

Department |

New Method |

Old Method |

Shift |

|

Minutes |

40% |

8% |

500% |

|

Hours |

43% |

40% |

108% |

|

End of Day |

7% |

28% |

-420% |

|

Day + |

3% |

12% |

-360% |

|

Varies |

0% |

4% |

n/a |

|

Not Report |

0% |

8% |

n/a |

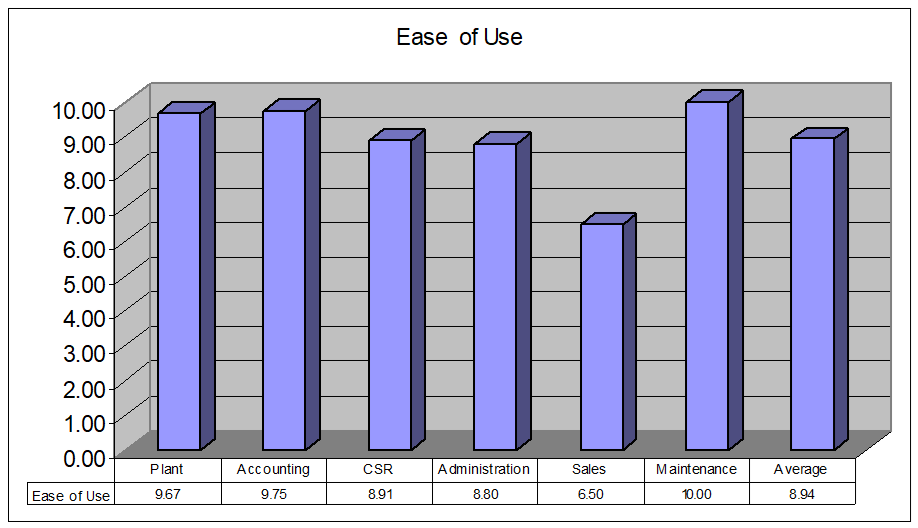

When asked to rate the reporting system’s ease of use on a scale of one to ten, the average score was 8.94. The Plant, Accounting and Maintenance employees rated higher with 9.67, 9.75 and 10.00 respectively, Customer Service and Administration matching the average with 8.91 and 8.80, and Sales reporting the lowest values with 6.50.

|

Department |

Ease of Use |

||||||||||

|

Plant |

10 |

10 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Accounting |

10 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CSR |

10 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

10 |

5 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

|

Administration |

10 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sales |

5 |

7 |

4 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maintenance |

10 |

10 |

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

Allingham, P. & O’Connor, M. (1992). MIS success: why does it vary among users? Journal of Information Technology, 7, 160-168.

Ambegaonkar, A.J. & Day, D. (2001). Development of cost-effective web-based outcomes research studies and disease management programs. Value in Health, 4, 182.

Bean, N.H. & Martin, S.M. (2001). Implementing a network for electronic surveillance reporting from public health reference laboratories: An international perspective. Perspectives, 7, 773-779.

Brakels, J., Van Daalen, E., Dik, W., Dopper, S., Lohman, F., Van Peppen, A., Peerdeman, S., Peet, D.J., Sjoer, E., Van Valkenburg, W. & Van de Ven, M. (2002). Implementing ICT in education faculty-wide. European Journal of Engineering Education, 27, 63-76.

Cullen, R. (1992). A bottom-up approach from down-under: Management information in your automated library system. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 3, 152-158.

Fernandez-Manjon, B., Fernandez-Valmayor, A. & Fernandez-Chamizo, C. (1998). Pragmatic user model implementation in an intelligent help system. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2, 113-124.

Grove, H.D. & Selto, F.H. (1990). The effect of information system intangibles on the market value of the firm. Journal of Information Systems, 4, 36-48.

Kelleher, R. (2000). A review of recent developments in the use of information communication technologies (ICT) in science classrooms. Australian Science Teachers Journal, 46, 33-39.

Kiesler, S. (2000). Troubles with the Internet: The dynamics of help at home. Human-Computer Interaction, 15, 323-352.

Martin, E.W. (1982). Critical success factors of chief MIS/DP executives. MIS Quarterly, 6, 1-9.

Moore, K. D. & Hopkins, S. (1992). Knowledge bases in teacher education: A conceptual model. Clearing House, 6, 381-386.

Turner-Bisset, R. (1999). The knowledge bases of the expert teacher. British Educational Research Journal, 1, 39-56.

Xu, X.M. & Kaye,

G.R. (2002). Knowledge workers for information support: Executives’ perceptions

and problems. Information Systems Mangement, 4, 81-88.

Appendix A

As you may know, a computerized error reporting system has been put into place to improve the method for reporting computer problems. In the past, all problems were reported by word-of-mouth, which took much longer and created needless waiting. In order to better analyze the usefulness of the Problem Change Control Reporting System (PCCRS), we would like you to answer the following questions.

1) Have you used the PCCRS system?

[ ] yes

[ ] no ( please skip to Question# 9 )

2) In you opinion, does the PCCRS system save you time? If so, how?

If you were present before the PCCRS system was in place, or you have worked elsewhere, where computer problems were reported by word-of-mouth, please answer the following three questions. If not, skip to Question# 6.

3) What benefits do you see in the PCCRS system? Drawbacks?

4) What is the average response time once a request is placed, before you receive attention?

[ ] within minutes

[ ] within the hour

[ ] by the end of the day

[ ] the next day or later

5) If the PCCRS system was not implemented, how would you report a computer problem, and how long do you estimate this would take.

6) Please rate the ease of use for the PCCRS system using the following scale:

Unusable [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] Intuitive

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

7) Was training worthwhile in order to better understand how PCCRS functions?

[ ] yes

[ ] no

8) Do you have any suggestions to improve the PCCRS system?

9) Please specify which department you are in.

[ ] Administration

[ ] Customer Service

[ ] Sales

[ ] Maintenance

[ ] Accounting

[ ] Plant